Nicolas Palmié1, Hélène Peyrière2, Claire Condemine-Piron1, Céline Eiden2, Jean-Pierre Blayac1,2

1Doping Preventing Medical Centres (AMPD) Languedoc-Roussillon, University Hospital of Montpellier, France

2Department of Medical Pharmacology and Toxicology, Addictovigilance Center, University Hospital of Montpellier, France

Address for reprints and Corresponding author:

Docteur Hélène PEYRIERE,

Service de Pharmacologie Médicale et Toxicologie, Hôpital Lapeyronie,

191 Avenue du Doyen Gaston Giraud, 34295 Montpellier Cedex 5, France.

Tel: 33-4-67-33-67-57

Fax: 33-4-67-33-67-51

e-mail: h-peyriere@chu-montpellier.fr

Keywords: Doping agents, Hot-line, Anabolic androgenic steroids, dependence

Conflict

of interest: No conflict of interest

exists in the preparation of our manuscript. None of the authors had any

conflict(s).

Abstract

In this study, 214 phone calls related to anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) and received by the French antidoping hot-line “Ecoute Dopage” during the period 2000-2008, were analysed. Fifteen different AAS (testosterone, nandrolone, methandrostenolone…) including clenbuterol were reported. Calls concerned information about doping AAS (28% of calls), side-effects (42%), risk for health (10%), psychological assistance (10%), legislation (2%)… Most calls came from fitness practitioners or bodybuilders (85%).

Among the 214 phone calls, 137 subjects (64% of calls) reported using doping AAS to increase muscular strength (76%), improve social life ability (15%), improve sporting ability (6%), and losing weight (3%). Eighty subjects (37%) reported at least one side-effect mainly uro-genital (40 cases) or psychic disorders (25 cases), both 15 cases. Among these 80 patients, 17 patients (21.25%) presented symptoms of AAS dependence, as defined in DSM-V classification (interpreted for diagnosing AAS dependence).

The abuse of

AAS in sport

is a public

health problem well known,

but data on the

dependence on AAS are sparser. However,

available data seem to show that dependence to AAS is a frequent complication

needing a management on both doping and dependence.

Introduction

Anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS), including testosterone and its synthetic derivatives, are widely used illicitly to gain muscle, enhance performance and physical appearance [1]. The consumer of AAS has changed over years, from competitive athletes to non-competing sportsmen wishing to improve their body image and gain social recognition [2]. This change in the consumer population, coupled with new ways of obtaining (internet), make it difficult to accurately estimate the consumption. Recent epidemiological studies suggest that at least 3% of young men in most western countries have used AAS at some time in their lives [3]. Moreover, epidemiological studies reveal that 15-30% of subjects who take AAS do not participate in any regular sport [4]. Doping is positioned between substance abuse and overmedication, and some of these users may develop a AAS dependence, with impossibility to stop the use despite side-effects, or withdrawal syndrome [2].

“Ecoute Dopage”, a french antidoping hot-line, is one of the national resources to fight against doping [5]. This telephone service was created in 1998, to listen, help and guide all sportspeople, coaches, parents and health professional distressed with doping. Psychologists and physicians answer questions about doping from anonymous callers involved in or exposed to doping. This antidoping hot-line represents an useful tool to assess the doping habits in general population.

The aim of this retrospective study was to analyze the doping calls concerning anabolic androgenic steroids, and to estimate those related to dependence item.

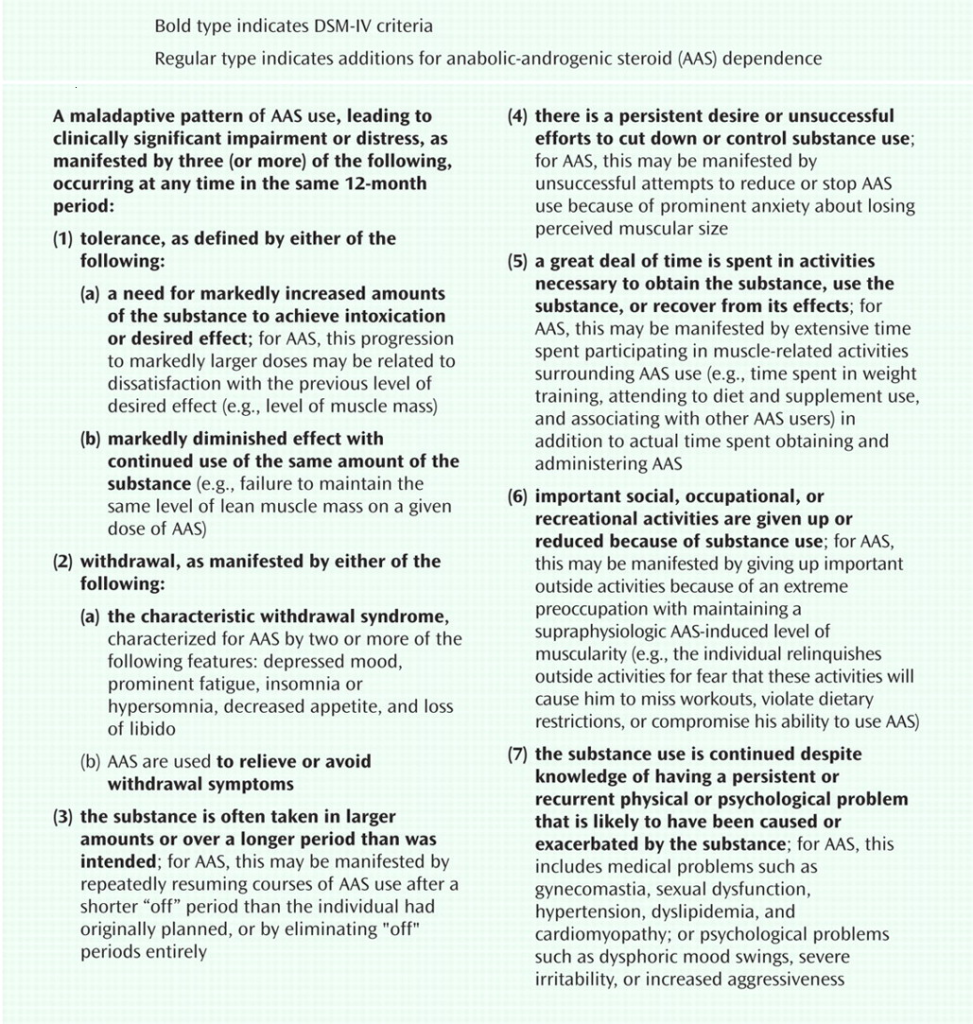

Methods: We reviewed all phone calls handled between 2000 and 2008 concerning AAS. Information collected included demographic data, reasons for the phone call, the anabolic androgenic steroid, characteristics of consumption (including the effects searched by the users of AAS), and physical and psychic side effects. Although Clenbuterol is not a steroid hormone, this beta2-adrenergic agonist possesses anabolic properties that increase muscle mass. Moreover, clenbuterol is considered as anabolic agents by the world anti-doping agency [6]. It was also included in the study. To assess the dependence to AAS, we used the items of dependence to AAS defined in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-V) (table 1) [7].

Results: Over the study period, the organization received 214 phone calls, concerning mainly men (97%), and adults (197 cases) with a median age of 23.5 years (data available for only 28 cases). Calls concerned information about side-effects of AAS (42% of calls), doping AAS (28%), risk for health (10%), psychological assistance (10%), legislation (2%)… Most calls came from bodybuilders or fitness practitioners (85%). In 15% of cases, the call was provided by the entourage of consumer.

Fifteen AAS were reported, the most commonly (more than 10 fold) being testosterone 61 cases, nandrolone 25 cases, methandrostenolone 22 cases, and stanozolol 12 cases. Clenbuterol was reported in 12 cases (figure 1). Among the 214 phone calls, 137 subjects (64% of calls) reported the reason for use AAS: to increase muscular strength (76%), improve social life ability (15%), improve sporting ability (6%), and losing weight (3%). Seventy-eight subjects (36%) reported characteristic of consumption: duration of the consumption per cycle (mean 3 weeks) and habits of administration (40% intravenous). Eighty subjects (37%) reported at least one side-effect: physical symptoms for 40 cases (headache, articular pains, acne, jaundice, sexual disorders, smaller testicles), psychic symptoms for 25 cases (anxiousness, aggressiveness, mood disturbances), both for 15 cases. In 11 cases of psychic side-effects, the call phone was made by the entourage, especially the spouse. Among 80 patients reporting symptoms related to AAS use, 17 (21.25%) presented symptoms of AAS dependence as defined in DSM-V classification (interpreted for diagnosing AAS dependence) [4]: tolerance (6 patients; 1 patient criteria 1a, 5 patients criteria 1b), withdrawal syndrome (5 patients criteria 2a). Other patients were diagnosed regarding criteria 5 for 2 patients, criteria 4 for 1 patient, criteria 7 for 1 patient, association of criteria 4 and 7 for 1 patient and association of criteria 5 and 7 for 1 patient. The diagnostic criteria for anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence are reported in table 1.

Discussion: The results of our study carried out between 2000 and 2008 show that, like in the literature, AAS uses seems to be a problem concerning mainly the men (97% of callers) [2].

Like in a Swedish study of 25,835 calls, received between 1993 and 2000 at their anti-doping hot-line, we found that the most commonly abused AAS were testosterone, nadrolone, methandienone and stanozolol [8]. In this study, 30% of the questions concerned AAS. Moreover, in this study as in ours, calls concerned clenbuterol in about 5% of cases that confirmed the importance of abuse of this drug. Questions concerning side-effects are by far the most frequent motive of calls in front of those for doping substances information. Moreover, questions relative to the health were usually associated with requests of help and psychological support. Side-effects reported by patients are well known and predictable from the pharmacological properties of AAS, especially urogenital and neuropsychic symptoms [1,8]. Several publications have reported the psychological and behavioral side-effects of AAS, especially after prolonged use and/or at higher doses than recommended, mainly by effect on serotoninergic system [1,9]. In 11 cases, the symptoms being enough severe, the call was made by the entourage or the spouse. However, the fact that many subjects call for information on the risks of side-effects or the link between consumption of AAS and side-effects observed, is positive. This shows that these consumers are aware of the risks of this consumption. This could be a recruitment bias, the subjects calling being those who have good knowledge about products, their effects and hot-line.

In our study, we found criteria of AAS dependence in 21 % (17/80) of the side-effects related call cases, 7% of the whole calls, with tolerance and withdrawal syndrome as main symptoms. In these cases, the subjects had criteria for dependence on AAS, but none mentioned the word “dependent” or “addicted”. The recognition of dependence to AAS is not easy on the phone but the call to “Ecoute dopage hot-line” could be a first step to support the consumption of AAS. A recent review of the literature has also documented the relation between AAS and dependence [2]. In these studies, about 30% of AAS users appear to develop a dependence syndrome characterized by chronic AAS use despite side-effects and withdrawal symptoms [7]. These data suggest that dependence is a frequent outcome of AAS use [3]. Most callers seems to take AAS for their anabolic effects (to gain muscle and lose body fat), and most of them described disorders of their body image. One possible risk factor for AAS dependence may be the presence of body image disorders, called “muscle dysmorphia’, in which individuals develop excessive preoccupations with their muscularity [10].

There are some limitations to our study. First, we conducted a retrospective study; there is always a lack of information depending on the person who took the call. Secondly, regarding to the criteria of dependence, the study was not conducted using a questionnaire about symptoms suggestive of dependence. The call was made mainly to a request for assistance or support to side-effects. Thus, some calls mentioning only libido disorders or mood disorders, while not fulfilling all the conditions of the DSM-V adapted to AAS were not considered as dependence.

Conclusion: The abuse of AAS in sport is a public health problem well known, but data on

the dependence on AAS are sparser.

However, available data seem to show that dependence to AAS is

a frequent complication needing a management on both doping and dependence. Information and education should be strengthened to

fight against doping.

References

- Sjöqvist F, Garle M, Rane A. Use of doping agents, particularly anabolic steroids, in sports and society. The Lancet 2008; 371: 1872-82.

- Kanayama G, Brower KJ, Wood RI, Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr. Anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: an emerging disorder. Addiction 2009; 104: 1966-78.

- Kanayama G, Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr. Illicit anabolic-androgenic steroid use. Hormones and Behavior 2010; 58: 111-121.

- Bahrke MS, Yesalis CE, Kopstein AN, Stephens JA. Risk factors associated with anabolic-androgenic steroid use among adolescents. Sport Med 2000; 29: 397-405.

- http://www.dopage.com/cas-dopage/ecoute-dopage-des-psychologues-en-premiere-ligne-75-48-3-274.html

- http://www.wada-ama.org/Documents/World_Anti-Doping_Program/WADP-Prohibited-list/WADA_Prohibited_List_2010_EN.pdf

- Kanayama G, Brower KJ, Wood RI, Hudson JI, Pope HG Jr. Issues for DSM-V: clarifying the diagnostic criteria for anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166: 642-5.

- Eklöf AC, Thurelius AM, Garle M, Rane A, Sjöqvist F. The anti-doping hot-line, a means to capture the abuse of doping agents in the Swedish society and a new service function in clinical pharmacology. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 59: 571-7.

- Quaglio G, Fornasiero A, Mezzelani P, Moreschini S, Lugoboni F, Lechi A. Anabolic steroids: dependence and complications of chronic use. Intern Emerg Med 2009; 4: 289-296.

- Pope Jr HG, Gruber AJ, Choi P, Olivardia R, Phillips KA. Muscle dysmorphia. An underrecognized form of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics 1997; 38: 548-557.

Table 1: DSM-IV substance dependence criteria, interpreted for diagnosing Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid dependence (DSM-V) [5]